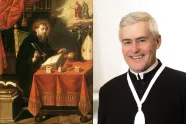

In connection with the publication of Pope Benedict XVI’s catecheses on the Church Father Augustine (in Norwegian) on katolsk.no, Father Elias Carr shares his reflections on the saint’s life, work and significance today. This series of catechesis was delivered by Pope Benedict XVI during his Wednesday audiences from January 9th to February 27th, 2008.

Father Elias Carr hails from the United States and is a Canon Regular of Saint Augustine at Stift Klosterneuburg in Austria. He has previously been chaplain at St. Paul’s Parish in Bergen, Norway, and is now Kämmerer at Klosterneuburg. He is also the author of the book I Came to Cast Fire: An Introduction to René Girard (Word on Fire, 2024).

From rhetorician to bishop

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430) was born in Thagaste in Roman North Africa and lived during the transition between two eras, the ancient and the medieval. He received an excellent classical education and was trained as a rhetorician in Milan.

― One has to keep in mind that this is no spin doctor or publicist, Fr. Elias points out.

― The philosopher Aristotle understood this profession as essential to fostering the community, because very few people are suited to learning truth on their own. Therefore, rhetoricians had a duty to present the truth through demonstrations, resting not only on words but also on their moral character.

Augustine practiced this profession at the highest level in the imperial government in Milan, but was not satisfied. His search for truth in philosophy and various religions also ended in disappointment.

― Into this existential crisis came a clear answer. Bishop Ambrose of Milan provided it through his word and example, says Fr. Elias.

Augustine received instruction and was eventually baptized by Saint Ambrose (c. 340–397) during the Easter vigil in Milan in 387. Ambrose is also a Church Father, but his influence is not as great as Augustine’s.

― What was it that made Augustine so great?

― Augustine’s baptism set him on a path of excellence, which he hoped to pursue in a community of like-minded philosophers. Yet, God had other plans for him. He was “forced” to accept ordination as a priest and then a bishop.

We can still read Augustine’s first sermons on the Beatitudes. He wrote extensively on various theological controversies that still shape our understanding of grace, the sacraments, and the Church. He was also a role model for community life in many religious orders that follow his Rule.

― For most of history, the City of God was seen to be his most important work. It is a defense of Christianity against its pagan critics, who saw the sack of Rome by the Goths as a sign of the weakness of the Christian God and the need to return to the old gods.

Fr. Elias recounts that Augustine witnessed the upheavals at the birth of a new world where the Gospel and antiquity, through the Church, would shape different peoples into a new Europe.

The invention of the individual

Pope Benedict highlights Augustine’s “Confessions, his extraordinary spiritual autobiography written in praise of God” as “his most famous work” (Catechesis, January 9th, 2008). Furthermore, he describes Augustine as “a contemporary who speaks to me, who speaks to us with his fresh and timely faith” (Catechesis, January 16th, 2008).

― What is it about Augustine’s Confessions that speaks to people today?

― The Confessions of Saint Augustine resonate with people today more than it did in the past because we are at the other end of a very long passage that resulted in the invention of the individual.

Fr. Elias explains that the concept of the individual, as we understand it today, arose as a result of the encounter between the Gospel and the West over many centuries. In faith and practice, the Church brought forth this new understanding of the person as a prerequisite for modernity, not as a product of it.

― Augustine reflects on his interior life. He shows us that God relates to us in many ways, sometimes in ordinary or even strange ways, such as the voice of a child telling him, “Take and read.” Augustine wrestles with the basic human questions, which gives his work a universal appeal.

The search for meaning and purpose characterizes most people’s lives. Given a seemingly endless number of possibilities, this search can also be a source of suffering. Fr. Elias points to the challenges faced by young people in particular.

― Even as they have achieved their legal majority and their physical maturity, they often seem overwhelmed emotionally and spiritually. This leaves them paralyzed before critical decisions about their lives, the very ones that give the meaning and purpose from which we live. Augustine shows us not only the value of the struggle, but more importantly, the answer.

The restless heart

The most famous quote from Augustine’s Confessions is: “You have made us for Yourself [Lord], and our hearts are restless until they rest in You” (I, 1:1). Recently, there has been a greater focus on the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the human heart, not least in Pope Francis’ 2024 encyclical Dilexit nos.

― What is the place of the heart in Augustine’s thinking?

― The French painter, Philippe Champagne, famously portrayed St. Augustine working at his desk. The saint turns his attention and body to the truth, which hovers over the Bible. The text he composes expresses his consuming love for God. Under his feet are the works of Pelagius and his followers, who maintained an optimistic view of human self-improvement.

Augustine knew that salvation cannot be achieved through hard work or education, Fr. Elias points out. The grace that Jesus makes available gives every human being the freedom to choose faith. Faith is therefore at once fully divine, a gift from God, and fully human, a free act in which one gives oneself back to God.

― The heart symbolizes the seat of thinking and willing that are ordered to the truth and the good. It also represents the emotions, that when rightly ordered, move one to seek the truth and choose the good. Resting in God is not a matter of inaction, but rather of full union with the Blessed Trinity, who is love.

A copy of this painting hangs in the Augustinian Canons’ chapel at Klosterneuburg.

Saint Augustine opened the way to devotion to the Sacred Heart as the locus of our personal encounter with the Lord. For Augustine, Christ’s wounded side is not only the source of grace and the sacraments, but also the symbol of our intimate union with Christ, the setting of an encounter of love.

Hope in times of crisis

“Despite being old and weary, Augustine stood in the breach, comforting himself and others with prayer and meditation on the mysterious designs of Providence,” says Pope Benedict (Catechesis, January 16th, 2008). Augustine lived in a time of crisis towards the end of the Western Roman Empire, yet he stayed with his people during the invasions of Vandals and Goths.

― What can we learn from Augustine’s trust in God in times of crisis?

― St. Augustine is a model of Christian trust because he recognized that we can only be happy in hope. The wish to secure happiness by worldly means is doomed to failure. The City of God is ordered to the communion of other-directed beings, whereas the city of man consists of beings who are self-directed.

Fr. Elias explains that the ecstatic (outward-directed) nature of the City of God has its origin in the mystery of the Trinity, while the self-absorbed nature of the citizens of the City of Man springs from the libido dominandi. Augustine uses this expression in two senses: the desire or lust to dominate, and at the same time, the lust that dominates.

― In other words, the self-centered person achieves his goal through the domination of others, whether persons or things. Yet, this desire itself oppresses the self-centered person, because he can never find rest or satisfaction in created goods. Not only is the world and everything in it transient, but we only find our fulfillment in God. Everything else falls short.

Instead, Augustine advises us to find happiness in this life through the hope of what is to come. In Book Five of The City of God, he writes about the character of Christian emperors:

[Christian emperors] are happy ... if they do all these things, not through ardent desire of empty glory, but through love of eternal felicity, not neglecting to offer to the true God, who is their God, for their sins, the sacrifices of humility, contrition, and prayer. Such Christian emperors, we say, are happy in the present time by hope, and are destined to be so in the enjoyment of the reality itself, when that which we wait for shall have arrived.

― This vision of political life also provides an antidote to those who wish to build heaven on earth, but in reality, only ensure hell on earth. Utopian programs, and the disappointment which their failures have wrought, has brought more misery in the world due to the lure of despair. Christians see this life for what it often is, the way of the Cross, but trust that at the end, there is a resurrection and a new creation.

Augustine’s Rule

Augustine’s Rule (Regula) for monastic communities is the oldest monastic rule in the Western Church and is used by several religious orders, including the Dominicans and Augustinians – both the Order of Saint Augustine (OSA) and the Canons Regular of Saint Augustine (Can.Reg.), to which Fr. Elias belongs.

― The canonical life is essential coterminous with the priesthood as it developed in the West. Priests lived under various customs and traditions. Over time it became hard to distinguish between monks and canons, as many monks became priests, and priests took on monastic practices.

Fr. Elias recounts that many monasteries of Canons, around the time of Pope St. Gregory VII’s reforms in the 11th century, began to adopt the Rule of St. Augustine and became Canons Regular of Saint Augustine (Canonicus Regularis S. Augustini). In 2033, it will be 900 years since the Augustinian Canons came to Klosterneuburg under the leadership of Blessed Hartmann.

The prologue of the Rule illustrates the saint’s vision for the community: “Before all else, dear brothers, love God and then your neighbor, because these are the chief commandments given to us.” He then briefly and precisely outlines the framework for realizing this vision of love for God and neighbor.

― The critical innovation for the canonical life was the shift from private property to common property as the corrective to the preceding period of decadence. The Rule of St. Augustine shapes our vocation profoundly as we try to follow his example today, says Fr. Elias.

The main purpose for you having come together is to live harmoniously in your house, intent upon God in oneness of mind and heart. Call nothing your own, but let everything be yours in common. Food and clothing shall be distributed to each of you by your superior.

An Augustinian Pope

Pope Leo XIV is also an Augustinian, although he belongs to a different community. As Fr. Robert Prevost, he was Prior General of the Augustinian Order from 2001 to 2013. From the beginning of his pontificate, he has emphasized Augustinian themes and quoted St. Augustine, and his coat of arms bears clear Augustinian symbolism.

― How can you see that Pope Leo XIV is an Augustinian?

― Our Holy Father, Pope Leo, has shown by his word and example his Augustinian spirit. For instance, his places a great deal of emphasis on unity.

Fr. Elias points to the Pope’s wish that “our first great desire be for a united Church, a sign of unity and communion, which becomes a leaven for a reconciled world” (Homily at the inauguration Mass, May 18th, 2025).

― In this statement, we can detect St. Augustine’ sweeping vision of history and beyond in the City of God. I think we can expect that Pope Leo will work to restore unity within the Church by healing division and wounds, as well as with other Christian churches.

Read more

- Word on Fire: Fr. Elias Carr